School Law

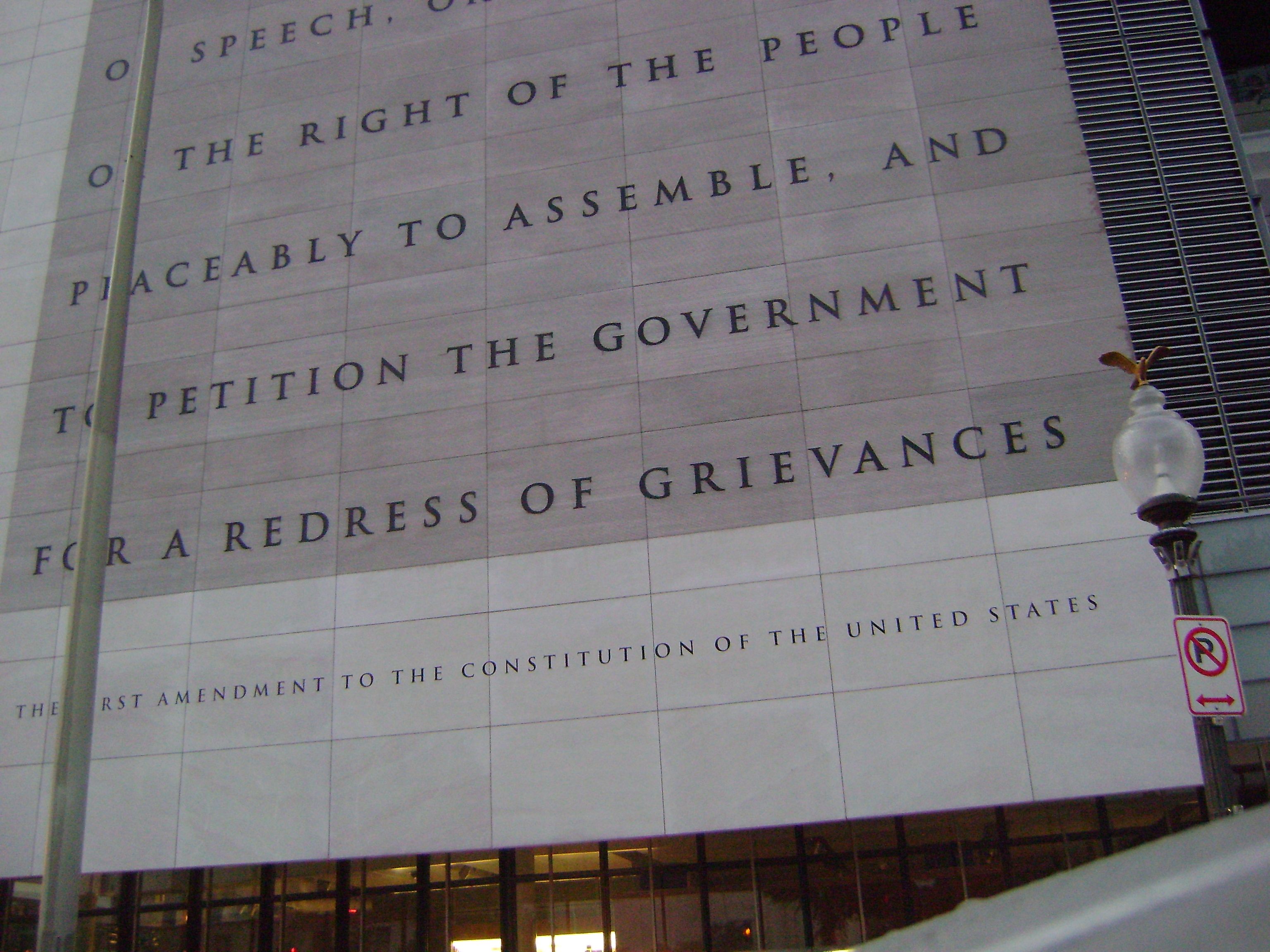

Schools and the First Amendment

Actions by the state in retaliation for speech activities of employees require due process under the federal constitution to determine “whether or not the speech or press interest is clearly protected under substantive First Amendment standards.” Board of Regents v Roth, 408 US 564 (1972).

Limitations of Speech in Schools

“It can hardly be argued that either students or teachers shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.” Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District, 393 U.S. 503, 506 (1969). Students in Tinker wore an armband to express opposition to the Viet Nam War. However, speech in the school setting has its limitations. “[C]onduct by the student, in class or out of it, which for any reason whether it stems from time, place, or type of behavior—materially disrupts classwork or involves substantial disorder or invasion of the rights of others is, of course, not immunized by the constitutional guarantee of freedom of speech.” Id. at 513.

Teachers do not enjoy the same protection as students. Judge Easterbrook has famously said, “A school system does not ‘regulate’ teachers' speech as much as it hires that speech.” Mayer v. Monroe County Community School Corp., 474 F.3d 477, 479 (2007). In Mayer a teacher was dismissed after telling her students that she opposed the war in Iraq. The school had a policy that teachers are not to state their view on the war.

No Academic Freedom

The Washington Supreme Court rejected a teacher’s First Amendment claim of academic freedom. “Course content is manifestly a matter within the board’s discretion.” Millikan v. Board of Directors of Everett School Dist. No. 2, 93 Wn.2d 522, 529 (Wash., 1980). Although “teachers should have some measure of freedom in teaching techniques employed, they may not ignore or omit essential course material or disregard the course calendar.” Id.

A federal district court overturned the dismissal of a teacher for writing a profane word on the blackboard as part of a lesson. “[W]hen a secondary school teacher uses a teaching method which he does not prove has the support of the preponderant opinion of the teaching profession . . . [for] a serious educational purpose, and was used by him in good faith the state may suspend or discharge a teacher for using that method but it may not resort to such drastic sanctions unless the state proves he was put on notice either by a regulation or otherwise that he should not use that method.” Mailloux v. Kiley, 323 F.Supp. 1387, 1392 (D. Mass., 1971)

Certain outrageous teacher conduct does not need to be in violation of a stated policy to be punished. One court upheld the termination of a teacher for showing an R-rated film to students even though the school had not established a policy regulating films shown to students. Krizek v. The Board of Education of Cicero-Stickney Township High School District No. 201, 713 F. Supp. 1131 (N.D. Ill. 1989). Although the teacher was trying to express a message through the film, he “offended the ‘legitimate pedagogical concerns’ of the school.. . . ” Id. at 1143. On the other hand, had the film not been indecent, the First Amendment generally would have protected the right of students to receive information from their teacher as long not in violation of a stated school policy. But if a “school had banned the [particular] film, the teacher would have had no First Amendment right to show the film because the school's decision was within its right to control the curriculum.” Id. at 1139.

Speech Criticizing School Policy

Concerning teacher speech outside of the classroom, courts "balance between the interests of the [employee], as a citizen, in commenting upon matters of public concern and the interest of the State, as an employer, in promoting the efficiency of the public services it performs through its employees." Pickering v. Board of Education, 391 U.S. 563, 568. In Pickering, a teacher’s criticism of the a policy of the school board was determined sufficiently a matter of public concern for constitutional protection. The speech need not be made in a public forum in order to be protected. “Neither the Amendment itself nor our decisions indicate that this freedom is lost to the public employee who arranges to communicate privately with his employer rather than to spread his views before the public. We decline to adopt such a view of the First Amendment.” Givhan v. Western Line Consolidated School District, 439 U.S. 410, 415-416 (1979). The teacher in Givahan had been dismissed for complaints she made to the principal concerning racial discrimination.

Pickering balancing does not always weigh on the side of free speech. In Hall v. Mayor & Dir. of Pub. Safety, 422 A.2d 797 (N.J. Super. App. Div. 1980) the criticism by a police officer of his superiors was insufficiently a matter of public concern compared to “the need to maintain discipline or harmony among co-workers.” Moreover, the constitution does not protect speech of an employee who is privy to a discretionary matter of public concern that “owes its existence to a public employee's professional responsibilities.” Garcetti v. Ceballos, 547 U.S. 410, 421 (2006).

A different standard is applied to policy-makers such as administrator. The Seventh Circuit has stated that “the government employer's need for political allegiance from its policymaking employee outweighs the employee's freedom of expression to such a degree that it obviates Pickering balancing.” Bonds v. Milwaukee County, 207 F.3d 969, 977 (7th Cir., 2000). A principal, whose plan for spending of a grant was rejected, was demoted for her subsequent opposition to the plan of her superiors. “The First amendment does not prohibit the discharge of a policy making employee when that individual has engaged in speech on a matter of public concern in a manner that is critical of superiors of their stated policies.” Vargas-Harrison v. Racine Unified School Dist., 272 F.3d 964, 971 (7th Cir., 2001).

Expression that Disgraces the Organization

The termination of a New York police officer was upheld for posing indecently showing her “uniform and police equipment, without authorization, for her personal commercial benefit, and [who] actively promoted the commercial product, in a manner that was likely to hold the department up to public ridicule.” Shaya-Castro v. New York City Police Dep’t., 233 A.D.2d 233 (N.Y. App. Div. 1st Dep’t 1996). Similarly the termination of a police officer at a function was upheld for indecent behavior while “sliding down an escalator bannister in a hotel. . . [r]ecognizing respondent's accountability to the public for the integrity of the Police Department.” Morrow v. Safir, 242 A.D.2d 217, 217-18 (N.Y. App. Div. 1st Dep’t 1997).

The Second Circuit upheld the dismissal of a teacher for setting up webpage displaying indecent pictures and for using this page to communicate with students with “unprofessional rapport.”Spanierman v. Hughes, 576 F.Supp.2d 292 (2008). In an unpublished NJ decision, Matter of O’Brien, (App. Div., 2013), the Appellate Division upheld the dismissal of a teacher for posting on her Facebook page, “I’m not a teacher — I'm a warden for future criminals!" She also posted, "They had a scared straight program in school — why couldn't [I] bring [first] graders?" She claimed that her statements were matters of public concern. “The ALJ and Commissioner found, however, that O'Brien was not endeavoring to comment on a matter of public interest, that is, the behavior of students in school but was making a personal statement, driven by her dissatisfaction with her job and conduct of some of her students. . . . [and] even if O'Brien's comments were on a matter of public concern, her right to express those comments was outweighed by the district's interest in the efficient operation of its schools.”

Student Speech

The “constitutional rights of students in public school are not automatically coextensive with the rights of adults in other settings.” Bethel v Fraser, 478 US 675, 682 (1986). The Bethel Court upheld the discipline of a student who had made lewd remarks in a school speech. Schools may also restrict students from “expressive activities that students, parents, and members of the public might reasonably perceive to bear the imprimatur of the school.” Hazelwood School Dist. v. Kuhlmeier,484 U.S. 260, 271 (1988). In Hazelwood the principal enjoined the publication of an article on teenage pregnanacy in a high school newspaper. The Court held that the student newspaper was sufficiently part of the school curriculum. A school does not have to promote a particular speech. A student newspaper is one of many “activities [that] may fairly be characterized as part of the school curriculum, whether or not they occur in a traditional classroom setting, so long as they are supervised by faculty members and designed to impart particular knowledge or skills to student participants and audiences.” Id.

In Morse v. Frederick, 551 U.S. 393 (2007), the Supreme Court upheld the discipline of student during a “school-sanctioned and school-supervised event.” Id. at 397. In Morse, students stood in the street outside of school as a group watching the Olympic Torch Relay. A student hoping to appear on television unfurled a banner that was interpreted by the principal to advocate the use of drugs. Although the “speech” did not cause a disruption, the discipline was upheld because of the “special characteristics of the school environment, and the governmental interest in stopping student drug abuse. . . .” Id.

As for student activity outside of school, in Thomas v. Board of Educ., 607 F.2d 1043 (2d Cir.1979) students were suspended for producing “a satirical publication addressed to the school community.” Id. at 1045. The Second Circuit sided with the students since there was no substantial disruption at school and the students “were very careful to distribute the periodical only after school and off campus, and the vast majority of their work on the publication was done in their homes, off campus and after school hours.” Id. The Third Circuit in Layshock v. Hermitage Sch. Dist., 650 F.3d 205, (3rd Cir., 2011) sided with a student who was suspended for publishing a fake internet profile of his principle. The school was not able to show a sufficient nexus between the speech and the school environment.